South Australian Medical Heritage Society Inc

Website for the Virtual Museum

Home

Coming meetings

Past meetings

About the Society

Main Galleries

Medicine

Surgery

Anaesthesia

X-rays

Hospitals,other organisations

Individuals of note

Small Galleries

Ethnic medicine

- Aboriginal

- Chinese

- Mediterran

A snapshot of the medical practitioners who provided care at the River Murray lock construction camps, 1915-1935

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Helen Stagg for her presentation on the medical care provided during the construction of the River Murray locks, given to the Society in November, 2017.

Lock construction on the Murray River is a little-known history in which my interest was ignited during my early years as I listened to my mother's stories of her childhood on the locks where her father worked as an engineman. Studies in oral history during my recent Masters in History gave me skills, which combined with years of archival research, culminated in my book "Harnessing the River Murray: stories of the people who built Locks 1 to 9, 1915-1935", marking the centenary of the commencement of the locking scheme.

The construction of locks and weirs along the Murray was an engineering enterprise on a massive scale with the object of ensuring reliable navigation and irrigation. South Australia's share, the first nine locks and weirs, was the focus of my research. These works spanned twenty years, involving the labour of huge numbers of men, transporting themselves and their families from one site to the next in remote regional locations. There they built small, temporary, relatively self-sufficient communities with a school and various sporting teams.

During Lock 1 construction, in January 1919, my grandmother Florence Rains, gave birth to my mother Evelyn, alone in a tent at Swan Reach, awaiting the arrival of the mid-wife. Childbirth was a vulnerable time for these river women and neo-natal death in the lock construction period was around ten times greater than in modern times. Of course, whooping cough, diphtheria, pneumonia and gastritis all took a toll on the children.

Accidents were commonplace in the very dangerous working conditions at the lock sites. Roughly one in ten of the accidents involved a back injury. This is not surprising since men would carry bags containing 186 pounds of cement and it had been known for men to handle as many as 400 bags of cement a day. The accident reports in the Engineering and Water Supply correspondence files state the details bluntly. e.g. "Thomas Price, driver on 72-foot derrick boat, had two fingers cut off but was given first aid and sent to the Kapunda Hospital for surgical attention". A few examples of accidents follow:

An accident in March 1929 at Lock 4 led to the death of Alex St. Clair, an engine driver. He was attending to the 12-inch centrifugal pump in the coffer dam, when he sustained severe lacerations and injuries to his head. He resumed work after spending two weeks in the Loxton Hospital, but he complained of constant pain in his head and committed suicide a few days later. Working at night posed risks with poor lighting, usually provided by acetylene lamps. At Lock 2 on 19 May 1926 at 8.30 pm, 52-year-old Donald Sheriff was working as a concrete mixer when he fell about 20 feet into a bay between the piers of the navigable pass, suffering severe internal injuries leading to 13 weeks off work.

Although more than 350 of the injuries were of a seemingly minor nature – including lacerations, bruises, strains, burns and cuts, piercing injuries due to a nail, piece of wire etc, could quickly escalate in severity due to sepsis. Engineman Richard Wills was "fixing the wire cable to orange-peel bucket used on the flying fox" in 1925 when he drove a piece of the wire rope into his left hand and septicaemia quickly set in. Although the accident report stated that he would need three weeks off work, he was dead just ten days later.

The South Australian Engineering and Water Supply Department entered into contractual arrangements both with a visiting doctor and a hospital at the nearest town, often many miles away from the lock site. The 'contract' system was in place at all locks but at Locks 7, 8 and 9, a resident medical officer was finally appointed. The contracted doctor was required to visit the lock on a weekly basis with an additional fee paid when attending cases of accident or emergency. Midwifery cases and those suffering from venereal disease or alcohol induced illness were excluded from these contracts, with such patients required to meet their own costs.

Many doctors were involved over the years with the locks, including Colin Nichol of Waikerie for Lock 1, Arthur Todd and later W L Smith of Morgan for Lock 2, Lance Hayward of Berri, Lock 3, Cecil Tanko and Ernest Alexander Joske of Loxton for Lock 4, John B Birch and George Harris of Renmark for Lock 5, George Harris for Lock 6, John Harris for Locks 7 and 8, Arthur Chenery of Wentworth and later AV Henderson for Lock 9. Travel was time-consuming for these busy rural doctors and when work at Lock 6 began in August 1927, Dr George Harris demanded an extra £100 because of the travelling distance from Renmark to reach the camp which was close to the South Australian border. This took his annual fee to £350. (Another doctor played a different role in 1930. Sir Henry Simpson Newland, the eminent surgeon, officially opened Lock 6 on January 14, 1930. Lock 6 is named the Simpson Newland Lock in honour of his father, a pioneer who tirelessly worked for the development of the Murray.)

In the early months at Lock 9, there were 100 people including 47 workers, their wives and children. Dr Chenery of Wentworth was appointed as visiting doctor after the people had petitioned for medical service provision. His fee was £8 per week, plus an additional £8 for special visits. When notified of illness or of an accident requiring urgent treatment, he would make a special visit 'within a reasonable time' and arrange admission to the Wentworth or Mildura hospital. Not owning his own car, Dr Chenery would hire a car for these visits. As at all the locks, the workers contributed, in this case, one shilling per week from their wages to defray the costs of the doctor's contract.

The winter of 1923 was unusually wet and the bush tracks leading to Lock 9 became impenetrable. There was no telephone at Lock 9 and essential calls had to be made from neighbouring Kulnine Station. When 32-year-old Maria Anspach developed post-influenza pneumonia, Dr Chenery was telephoned in the evening, but being unable to obtain a car, he gave instructions for her care over the phone. However, she was dead before morning. This tragedy mobilised the community and just seven days afterwards, a petition signed by eighty-five people demanded improved medical care, including a resident nurse at the camp and a government car to be stationed at the lock to drive cases of serious accidents and illness to hospital. They added that Dr Chenery had indicated his unwillingness to continue at the lock and complained that his weekly visits had been interrupted during the winter. A departmental inquiry followed into the events around Mrs Anspach's death, including Dr Chenery's attention to his duties at the lock. Chenery claimed he had given the lock residents the best attendance it was "humanly possible to give during one of the worst winters on record and over a road that was considered to be the worst in the district". Regarding the report that he no longer wished to continue as the contracted doctor, he said that when asked by a resident if he had forgotten them, he had replied, "Well if anyone else wants the job they can have it". This was after he had just completed "a bone racking journey of three hours duration to cover the 28 miles". He then submitted his resignation.

Following Chenery's resignation, the Engineer-In-Chief's Department decided to appoint a resident medical officer, Dr AV Henderson from Mildura on an annual salary of £500. The Lock 9 community was ecstatic and formed a hospital committee to raise funds to furnish, equip and maintain a small cottage hospital and to pay the wages of a nurse. A busy round of concerts, film nights and fancy-dress balls contributed funds to the cause.

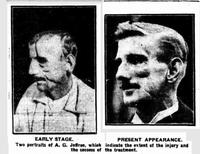

A frightening pit collapse at Lock 5 on 23 April 1923 nearly claimed the lives of several men. The so-called 'deadman', a heavy log which anchored a stay-wire to support the gigantic wooden tower nearby, had just been placed into a 25 feet long and 14 feet deep pit when one of the men, seeing a crack in the wall of the pit, shouted a warning. The workers sprang to one end as ten tons of earth came crashing down. Dr John Birch from Renmark arrived during the rescue as men were furiously shovelling to free the trapped workers Richard Fitzpatrick, Albert Jeffree, and Stan Jury. Jury, badly bruised and shaken, was the first retrieved and was sent to the Renmark hospital for observation. Fitzpatrick and Jeffree were almost completely covered. When Albert Jeffree was dragged clear, his face and head were terribly mutilated with compound fractures to his face, and his scalp was badly stripped. It took almost an hour before Fitzpatrick was brought to the surface in an exhausted state and in great pain from compound fractures to his leg.

Both Jeffree and Fitzpatrick suffered greatly and endured extended periods off work. Richard Fitzpatrick returned to work after 15 months. Jeffree's case was written up in the Adelaide media. This news article headed "Head split in twain and still lives. Man's grim fight against great odds", told of Jeffree's 14-month-long journey to recovery. When interviewed in Adelaide, he described the 13-inch head wound, starting on the top of his skull, going over his forehead and left eye, down the left cheek to just beneath his jawbone. His left ear and cheek were almost severed from his face, and he recounted how Dr Birch had held the separated section in his hands and scrubbed it before performing a grafting operation. Nurse Irene Lucy, who cared for him in Renmark Hospital, continued to care for him in Adelaide and they later married.

When work started at Lock 7 in 1930 Dr George Harris of Renmark who previously had been contracted to Lock 5 and 6, provided a visiting service when needed but the distance was 40 miles. In March 1931, newspaper advertisements appeared for a resident medical officer at a salary of £450 per annum to serve both Locks 7 and 8 since they were only 14 miles apart.

Crowded living conditions in the tiny houses in the camps allowed for easy transmission of diseases like diphtheria, and the 1931 outbreak in the Lock 7 camp was devastating. On 11 May 1931, teacher John Moloney sent a telegram with the tragic news:

"Eight grades, 100 children all in one room, 70 ft. by 20 ft. Curtain division. Many sore throats, two deaths. No swabs taken; several grades affected."

Dr Harris ordered the closure of the school for a minimum of ten days and the epidemic brought media attention to the problem of not having a resident doctor as this letter to the Adelaide Advertiser shows:

"Diphtheria has broken out at Lock 7 where there are more than 200 children. I hope the government will station a resident doctor there. It is hard for parents to have to take their sick children nearly 40 miles and then find it is too late to save their lives."

The brother of Renmark's Dr George Harris, Dr John Harris, who had just returned from five years post-graduate work in England, was finally appointed as resident medical officer at Lock 7 and began duty on 25 May 1931. When a four-roomed cottage became vacant in July 1931 Dr Harris wrote suggesting its use as a cottage hospital. This would allow more suitable treatment as several of the diphtheria cases were in two or three-roomed bag-walled houses, the only warmth being a fire in the kitchen and no way of isolating the patient from other family members. Harris's request was finally approved, and from September 1931 Isabelle Arnold from Pinnaroo was appointed as nurse on a salary of £120 per annum with board and lodging.

Early in 1932 the Lock 7 and 8 Cottage Hospital Committee took control, and paid the nursing sister's salary from the men's weekly deductions. Just as they had at Lock 9, the workers formed a fundraising committee and held many social events and balls to assist in the running of what they saw as an essential part of their temporary town.

Over the next two years, the hospital provided care for the residents at Locks 7 and 8 until in February 1934 as the works wound down, Dr Harris asked to terminate his contract and it was arranged for Dr Davis of Werrimull to visit the works till the completion at the site.

Medicine is one of those careers which allows you to travel and take on a variety of experiences. The doctors who attended patients at the lock construction sites had a rather unique experience at an important stage of our nation-building and these few stories comprise part of the little-known history of the people who built the locks and weirs along the River Murray.

Submitted by Helen Stagg, author of "Harnessing the River Murray: stories of the people who built Locks 1 to 9, 1915-1935", (pub 2015, Digital Print, Gilles St, Adelaide, SA.)

Appendix

Weirs have long been used to change the depths of waterways, making it easier for vessels to navigate, and also acting as dams to provide irrigation and drinking water. Of course, they also block passage, so locks became necessary.

Locks allow vessels to travel between stretches of water at different heights, for example, between a river and a canal system, or when bypassing a rapid. The simplest lock, a flash lock, is believed to have first been used in China around 50 BCE. This type of lock was essentially a removable section in a weir through which a boat could pass. Travelling upstream was fairly safe, as the vessel needed to be pulled through. Downstream passage was more dangerous due to the rapid flow and potentially shallow water after the exit.

It wasn't until 984 CE that a second gate was added, creating the safer pound lock. Two guillotine gates were placed in a closed stretch of water on the Grand Canal, near Huai-yin in China. This allowed a more controlled transfer of water into and out of the lock, and far safer passage. Locks with two gates forming a V-shape pointing upstream are believed to have been invented by Leonardo da Vinci around 1487. One advantage of these locks is that the difference in water levels helps to keep the gates firmly shut.

In the late 19th C, locks on the Murray were envisioned to make the river easier to navigate, rather than for use in irrigation. It was later, with the droughts in 1902 and 1913, that irrigation became the more important function. River trade routes all were all but abandoned in favour of roads by the 1930's, but the locks are still a vital component of our irrigation and drinking water supplies.

For a more detailed history of the development of the river Murray locks, you may like to read this page.